Creating a simple JIT compiler in C++

June 03, 2014

When we are designing a programming language, we generally have to decide whether it will be compiled or interpreted. Compilation has the obvious benefit of producing code that is even orders of magnitude faster than the purely interpreted counterpart. On the other hand, interpreters tend to be more easily implemented, since we can implement them in a high-level programming language without knowing the platform specific details, such as the machine code, ABI and the executable format. It also allows for easy introspection, dynamic typing, eval statements et cætera. JIT (Just-in-time) compilation combines the benefits of both. When code is compiled as needed we retain the flexibility of interpreted languages along with the speed of compiled code.

In this article we will make a simple JIT compiler for parametrized mathematical expressions for x86-64 platform, written in C++.

Reverse Polish notation

(1 + 1) * (2 / 3) in standard notation corresponds to 1 1 + 2 3 / * in RPN

Expressions in the reverse Polish notation are more natural for a computer than the standard infix notation, since they are evaluated using a stack, which is a ubiquitous data structure. The other reason I chose RPN is that I have a special affinity for it, having designed a programming language based on it. The evaluation algorithm is very simple:

- Read the tokens (numbers, operators) one by one

- If the token is a number, put it on the stack

- If the token is an (binary) operator, pop the two topmost elements off the stack, perform the operation on them and push them back on the stack

- If the expression is well formed, the stack will contain only one element which will be the result

A simple RPN evaluator for parametrized RPN expressions can thus be written like this (we could use std::stack but we deliberately avoid heap allocation for now):

double rpn(char const* expression, double x)

{

array<double, 128> stk;

int depth = 0;

for (; *expression; ++expression)

{

if (depth >= 127)

throw runtime_error("Too much nesting");

if (isdigit(*expression) || (*expression == '.') ||

(*expression == '-' && isdigit(*(expression + 1))))

{

char* new_expression;

stk[depth] = strtod(expression, &new_expression);

expression = new_expression;

++depth;

}

else if (*expression == 'x')

{

stk[depth] = x;

++depth;

}

else if (*expression > 32)

{

switch (*expression) {

case '+': stk[depth - 2] += stk[depth - 1]; break;

case '*': stk[depth - 2] *= stk[depth - 1]; break;

case '-': stk[depth - 2] -= stk[depth - 1]; break;

case '/': stk[depth - 2] /= stk[depth - 1]; break;

default: ;

}

--depth;

}

if (*expression == '\0')

break;

}

return stk[0];

}Straightforward enough, the problem is that this evaluator is relatively slow since it has to parse the expression string every time evaluates the expression. For example - on my laptop (Intel Core i7 2640M @ 2.8 GHz), it takes around 9.5 seconds to evaluate an expression with 100,000,000 tokens. Of course this can be made significantly faster by various means, for example by first parsing the string into bytecode, but we will skip this step and go directly to machine code compilation.

Executing arbitrary machine code

Ahead-of-time compilation is usually performed in three stages. First the compiler generates the machine code from compilation units and generates object files. Then a linker combines the object files and external statically linked libraries to generate an executable file which is saved on a disk. When we want to execute, a program loader loads the executable into memory, sets up stack space, initializes environment data and registers and then transfers the execution to the program’s entry point (such as a main() function in C/C++).

JIT compilers skip the intermediary stage of linking and load the compiled program directly into memory. We will be be constructing the machine code somewhere, so let us define - for convenience’s sake - a helper class that will allow us to easily inject opcodes of arbitrary size (8, 16, 32, 64 bytes):

using namespace std;

class code_vector : public vector<uint8_t>

{

public:

/*

This enables us to push an arbitrary type as an immediate

value to the stream

*/

template<typename T>

void push_value(iterator whither, T what)

{

auto position = whither - begin();

insert(whither, sizeof(T), 0x00);

*reinterpret_cast<T*>(&(*this)[position]) = what;

}

};Due to security precautions on modern OSes, we cannot execute arbitrary code in memory. It has to reside in a memory page that has the NX bit disabled. Fortunately, it very easy to allocate an exectutable chunk of memory. On Windows, we would call something like:

void* ptr = VirtualAlloc(0, size, MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);and on Unix:

void* ptr = mmap(NULL, size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC,

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANON, -1, 0);Before we continue, let me stress that what we just did is dangerous. We don’t want the memory to be both writeable and executable at the same time as this opens up a rather large attack surface for buffer overrun attacks. Therefore, we will first write everything we want and only then mark it executable, which is not any harder.

Even though we are leaving the safety and comfort of C++ by writing the machine code, we would still like a nice way of wrapping our functionality. We will write a x_function class with a similar interface as std::function.

First the memory allocation, protection and deallocation routines:

template<typename> class x_function;

template<typename R, typename... ArgTypes>

class x_function<R(ArgTypes...)>

{

bool executable_;

size_t size_;

void * data_;

public:

void set_executable(bool executable)

{

if (executable_ != executable)

{

#ifdef _WIN32

DWORD old_protect;

VirtualProtect(

data_, size_,

executable ? PAGE_EXECUTE_READ : PAGE_READWRITE,

&old_protect

);

#else

mprotect(data_, size_,

PROT_READ | (executable ? PROT_EXEC : PROT_WRITE));

#endif

executable_ = executable;

}

}

x_function(size_t size) :

executable_(false),

size_(size)

{

if (size == 0) { data_ = nullptr; return; }

#ifdef _WIN32

data_ = VirtualAlloc(0, size, MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_READWRITE);

#else

data_ = mmap(NULL, size,

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANON, -1, 0);

#endif

}

x_function(void* data, size_t size) :

x_function(size)

{

memcpy(data_, data, size);

set_executable(true);

}

~x_function()

{

#ifdef _WIN32

VirtualFree(data_, 0, MEM_RELEASE);

#else

munmap(data_, size_);

#endif

}

/* ... */Next we implement basic copy and move semantics. For demonstration purposes, we will not be overly concerned with how efficiently memory management is handled. For now, let the memory be actually copied when the object is copied, but in reality some form of reference counting is more reasonable, since the executable code will not be changing much once it is committed to memory.

/* ... */

void swap(x_function& other)

{

using std::swap;

swap(executable_, other.executable_);

swap(size_, other.size_);

swap(data_, other.data_);

}

x_function() : x_function(0) {}

x_function(const x_function& other) : x_function()

{

x_function copy(other.size_);

memcpy(copy.data_, other.data_, other.size_);

copy.set_executable(other.executable_);

swap(copy);

}

x_function(x_function&& other) : x_function() { swap(other); }

x_function& operator=(x_function other)

{

swap(other);

return *this;

}

x_function(code_vector::iterator begin, code_vector::iterator end) :

x_function(&*begin, end - begin) { }

/* ... */And now the most interesting part of our class - the operator():

/* ... */

template<typename... RArgTypes>

R operator()(RArgTypes&&... args) const

{

return reinterpret_cast<R(*)(ArgTypes...)>(data_)(

forward<RArgTypes>(args)...);

};

};Since it may look slightly esoteric on the surface, let us break it down:

- First it casts the

data_pointer to the function pointer of the type thex_functionwas instantiated with. E.g. if we havex_function<int(int)>, it will cast the pointer toint (*) (int)pointer type. - It invokes the function referenced by the function with the parameters provided to it. The rest of the clutter is just for perfect forwarding made possible by rvalue references and variadic templates.

This is it! Now we can write our first function. The remainder of this will involve x86-64 machine code and assembly with which I admit I don’t have a tremendous amount of experience. So if you spot any error or inelegance, please let me know, so I can improve it.

“Actual” C++ closures

Simply put, closures are functions that “capture” one of their arguments by return another function whose functionality depends on it. Since C++11, we can create closures in an elegant manner with lambdas:

function<int(int)> adder(int n)

{

return [n] (int m) { return n + m; };

}

auto f = adder(42);

cout << f(10) << endl // 52

<< f(-1); // 41Usually the closures are implemented by storing the captured value somewhere and later accessing it. Using our class we can create “actual closures” i.e. functions whose entire functionality is dependent on the parameter. Without further ado, the “actual closure” equivalent is:

x_function<int64_t(int64_t)> real_adder(int64_t value)

{

code_vector code;

code.insert(code.end(), { 0x48, 0xB8 });

code.push_value(code.end(), value);

#ifdef _WIN32

code.insert(code.end(), { 0x48, 0x01, 0xC8, 0xC3 });

#else

code.insert(code.end(), { 0x48, 0x01, 0xF8, 0xC3 });

#endif

return x_function<int64_t(int64_t)>(code.begin(), code.end());

}

auto f = real_adder(42);

cout << f(10) << endl // 52

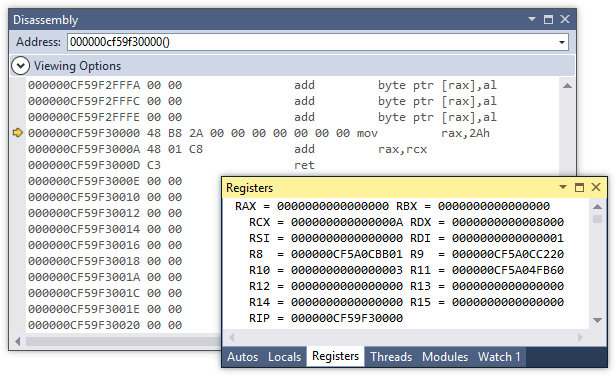

<< f(-1); // 41Here is the disassembly of the code it produces:

The function does exactly as the disassembly above shows. It moves the hardcoded value to the rax register, then it adds the contents of rcx (or rdi on UNIX) and then returns. Granted, it is not as elegant as the lambda version above (and it shouldn’t be any faster), but it serves to illustrate the principle we will extend for our RPN compiler.

Calling conventions

We have seen that there was some conditional compilation in the previous snippet. The reason for this is a different calling convention on Windows and Unix-like operating systems.

Calling convention is a a standard specifying how functions interact on an machine code level in an interoperable way. It varies greatly between different system architectures, and even among different OSes on the same architecture. It specifies how the parameters are passed when calling a function and who (caller or callee) takes care of stack unwinding. 32-bit x86 architecture knows a plethora of calling conventions (cdecl, stdcall, pascal, fastcall, …) but on x86-64, there is generally just one (with minor differences among OSes). Since the JIT we are building targets x86-64 with Windows and Linux, let us highlight the important points:

- The callee cleans up the stack

- Some integer and pointer (reference) parameters are passed in registers, the others on stack

- On Windows first 4 parameters in

rcx,rdx,r8andr9 - On Unix first 6 parameters in

rdi,rsi,rdx,rcx,r8, andr9

- On Windows first 4 parameters in

- Integer/reference return value is always passed in

rax - Floating point parameters are passed in SSE registers, the others on stack:

- On Windows first 4 parameters in

xmm0,xmm1,xmm2andxmm3 - On Unix first 8 parameters in

xmm0-xmm7

- On Windows first 4 parameters in

- Floating point return value is always passed in

xmm0 - On Windows certain registers must be preserved across function calls (

xmm5-xmm7)

Full details on x86-64 calling conventions can be found here (for Windows) and in the System V ABI (for Unix).

Large datatypes are usually passed by reference. We can just as easily do that, for example like this (persumes Windows calling convention):

x_function<void(int64_t&)> real_adder_by_ref(int64_t value)

{

code_vector code;

code.insert(code.end(), { 0x48, 0xB8 });

code.push_value(code.end(), value);

code.insert(code.end(), { 0x48, 0x01, 0x01, 0xC3 });

/*

movabs rax, %(value)

add QWORD PTR [rcx],rax

ret

*/

return x_function<void(int64_t&)>(code.begin(), code.end());

}

int64_t x = 10;

real_adder_by_ref(42)(x);

cout << x; // 52We can use C++ references or pointers interchangeably - under the hood they correspond to exactly the same machine code but in my opinion references have a cleaner syntax.

Compiling RPN expressions to machine code

Now we have everything we need to create a compiler for RPN expressions. We define a function rpn_compile(char const*) that takes a RPN expression string (parametrized with x and returns a function that maps x to the evaluated expression’s value. The machine code will be a simple sequence of numbers and operations without any jumps (since there is no need for them). We have 8 registries xmm0-xmm7 at our disposal and we will try to compute the expression without the main stack but in case that the nesting level is too high and 8 slots do not suffice, we will store the intermediate values there.

First we define some macros for commonly used x86-64 instructions. These macros inject their respective opcodes into our code_vector:

x_function<double(double)> rpn_compile(char const* expression)

{

code_vector code;

vector<double> literals;

// Some macros for commonly used instructions.

auto xmm = [](uint8_t n1, uint8_t n2) -> uint8_t

{ return 0xC0 + 8 * n1 + n2; };

auto pop_xmm = [&](uint8_t whither) {

code.insert(code.end(), { 0xF3, 0x0F, 0x6F,

(uint8_t)(0x04 + whither * 8), 0x24, 0x48, 0x83, 0xC4, 0x10 });

};

auto push_xmm = [&](uint8_t whence) {

code.insert(code.end(), { 0x48, 0x83, 0xEC, 0x10,

0xF3, 0x0F, 0x7F, (uint8_t)(0x04 + whence * 8), 0x24 });

};

auto operation = [&](uint8_t op, uint8_t n1, uint8_t n2) {

code.insert(code.end(), { 0xF2, 0x0F, op, xmm(n1, n2) });

};

auto movapd_xmm = [&](uint8_t n1, uint8_t n2) {

code.insert(code.end(), { 0x66, 0x0F, 0x28, xmm(n1, n2) });

};

auto load_xmm = [&](uint8_t n, int32_t offset) {

code.insert(code.end(), { 0x66, 0x0F, 0x6F,

(uint8_t)(0x81 + n * 8) });

code.push_value<int32_t>(code.end(), 16 * offset);

};

/* ... */Their meaning is as follows:

| Macro | Meaning |

|---|---|

xmm |

Gives the opcode signifying a pair of xmm{n1},xmm{n2} registers |

pop_xmm |

Pops the floating point value from the stack into the xmmN |

push_xmm |

Pushes the floating pint value from the xmmN onto the stack |

operation |

Performs one of the four arithmetic operations, in the xmm{n1},xmm{n2} registers |

movapd |

Copies the contents of xmm{n2} into xmm{n1} |

load_xmm |

Loads the literal from some position in memory to the xmmN |

pop_xmm and push_xmm are implemented by manually in-/decrementing the stack pointer and copying the value.

Let us examine how the constant values will be stored. Since xmmN register are 128 bit (16 = 10(16) bytes) registers that contain two packed double-precision floating point values, we will store the constant values separately, after the execution code and load it from said memory when we need it. To this end we will use RIP-relative addressing and store the pointer to the beginning of data section in the rcx pointer at the beginning of the routine and then load the data from offsets relative to it - for example:

# Function entry point

000000A0614C0000 lea rcx, [rip + 0x59] # We store the beginning of data

...

000000A0614C0022 movdqa xmm1,xmmword ptr [rcx] # We move the 1st constant to xmm1

000000A0614C002A movdqa xmm2,xmmword ptr [rcx+10h] # We move the 2nd constant to xmm2

...

000000A0614C0055 ret # End of the function

...

# Beginning of data section

000000A0614C0060 00 00

000000A0614C0062 00 00

000000A0614C0064 00 00

000000A0614C0066 0F 3F

000000A0614C0068 00 00

000000A0614C006A 00 00

000000A0614C006C 00 00

000000A0614C006A 00 00The constants have to be aligned on the 16-byte boundary so we can load them with movdqa that is more efficient than its unaligned movdqu counterpart. We will inject the lea instruction when we will have generated the rest of the code, since we have to know the total code length.

As I mentioned in the previous section, Windows ABI requires us to preserve the registers, so we push them on the stack to be restored when we are done:

/* ... */

#ifdef _WIN32

push_xmm(5); push_xmm(6); push_xmm(7);

#endif

/* ... */The rest of the code is a straightforward modification of the algorithm we had earlier. At each point we keep track the current depth and if we are less than 6 levels high, we just shuffle the registers around and compute the operations on them. If depth exceeds 6 (we need xmm6 and xmm7 for calculating, so we cannot use them as a part of stack), we push or pop the values onto/from the main stack.

If we encounter the literal, we push the load instruction with the appropriate offset (which is a multiple of 16) into the code. The actual literal is stored separately to be inserted in the data section:

/* ... */

for (; *expression; ++expression)

{

if ( isdigit(*expression) || (*expression == '.') ||

(*expression == '-' && isdigit (*(expression+1)) ))

{

char* new_expression;

literals.push_back(strtod(expression, &new_expression));

expression = new_expression;

// We copy the data from the literal table to the appropriate

// register

load_xmm(min(depth + 1, 6), literals.size() - 1);

if (depth + 1 >= 6)

push_xmm(6);

++depth;

}

/* ... */By the calling convention, we have received the parameter x in xmm0 register. So in our case, the stack begins at xmm1 and when we want to use the parameter, we just move it to the appropriate place.

/* ... */

else if (*expression == 'x')

{

// The parameter is already in this register, so we just

// copy/push it.

if (depth + 1 >= 6)

push_xmm(0);

else

movapd_xmm(depth + 1, 0);

++depth;

}

/* ... */If we read an operator, we push the appropriate arithmetic instruction:

/* ... */

else if(*expression > 32)

{

// If we have fewer than 2 operands on the stack, the

// expression is malformed.

if (depth < 2)

throw runtime_error("Invalid expression");

if (depth >= 6)

pop_xmm(6);

if (depth > 6)

pop_xmm(7);

// Perform the operation in the correct registers

int tgt_reg = min(depth - 1, 6);

int src_reg = min(depth, 7);

switch (*expression) {

case '+':

operation(0x58, tgt_reg, src_reg);

// addsd xmm{tgt}, xmm2{src}

break;

case '*':

operation(0x59, tgt_reg, src_reg);

// mulsd xmm{tgt}, xmm2{src}

break;

case '-':

operation(0x5C, tgt_reg, src_reg);

// subsd xmm{tgt}, xmm2{src}

break;

case '/':

operation(0x5E, tgt_reg, src_reg);

// divsd xmm{tgt}, xmm2{src}

break;

default:;

}

// If the register stack is full, we push onto the main stack.

if (depth > 6)

push_xmm(6);

--depth;

}

// If strtof moved the pointer to the end.

if (*expression == '\0')

break;

}

/* ... */When the above code finishes execution, we have result stored in xmm1. So we move it into the xmm0 (as specified by the calling convention), restore the upper registers that we stored earlier and return from the function:

/* ... */

// If there is to little or too much left on stack.

if (depth != 1)

throw runtime_error("Invalid expression");

// The return value is passed by xmm0. Now we no longer need

// to hold onto the value for x.

movapd_xmm(0, 1);

#ifdef _WIN32

// We restore the XMM5-7 register state.

pop_xmm(7); pop_xmm(6); pop_xmm(5);

#endif

code.push_back( 0xc3 ); // ret

/* ... */That’s it! The only thing left to do is to insert the constant values and calculate the offset.

/* ... */

// +7 since we are going to insert a lea instruction

int32_t executable_size = code.size() + 7;

// Align on the 16-byte boundary:

executable_size = 15 + executable_size - (executable_size - 1) % 16;

code.insert(code.begin(), { 0x48, 0x8D, 0x0D });

code.push_value<int32_t>(code.begin() + 3, executable_size - 7);

code.insert(code.end(), executable_size - code.size(), 0x00);

/*

We place all the floating point literals AFTER the code.

*/

for (double val : literals)

{

// The registers are 128-bit but we are only

// interested in the lower half

code.push_value<double>(code.end(), val);

code.push_value<double>(code.end(), 0);

}

return x_function<double(double)>(code.begin(), code.end());

}

We can now compile expressions and later evaluate them for a given parameter:

reciprocal = rpn_compile("1 x /");

for (double x = -1; x <= 1; x += 0.001)

{

cout << "1/" << x << " = " << reciprocal(x) << endl;

}In this concrete case, the code compiles to the machine code seen below:

000000F41BEB0000 00 00 lea rcx,[0F41BEB0060h]

# Save the register values

000000F41BEB0007 sub rsp,10h

000000F41BEB000B movdqu xmmword ptr [rsp],xmm5

000000F41BEB0010 sub rsp,10h

000000F41BEB0014 movdqu xmmword ptr [rsp],xmm6

000000F41BEB0019 sub rsp,10h

000000F41BEB001D movdqu xmmword ptr [rsp],xmm7

# Actual calculation

000000F41BEB0022 movdqa xmm1,xmmword ptr [rcx]

000000F41BEB002A movapd xmm2,xmm0

000000F41BEB002E divsd xmm1,xmm2

000000F41BEB0032 movapd xmm0,xmm1

# Restore the register values

000000F41BEB0036 movdqu xmm7,xmmword ptr [rsp]

000000F41BEB003B add rsp,10h

000000F41BEB003F movdqu xmm6,xmmword ptr [rsp]

000000F41BEB0044 add rsp,10h

000000F41BEB0048 movdqu xmm5,xmmword ptr [rsp]

000000F41BEB004D add rsp,10h

000000F41BEB0051 ret

# The rest is data. The constant 1.0 resides at address 0F41BEB0060Summing up

Of course we now want to know just how much was gained by the extra effort of compiling the function. The benchmark I mentioned before was an output from a small routine that generates random expressions of specified length. It turns up that the speed-up is quite significant, for an expression with 100,000,000 tokens (compiled with Intel C++ Compiler 15):

| Stage | Time |

|---|---|

| Generation of a random expression | 42.4s |

| Evaluation (interpreted) | 9.62s |

| Compilation | 16.9s |

| Evaluation (compiled) | 0.113s |

This is a speed-up of almost 8500%. Of course, this is not a completely fair comparison - both interpreted and compiled calculation could be optimized further and evaluating a random expression 100,000,000 tokens long is hardly a decisive benchmark of real-world performance. But the point stays the same - compilation can yield significant performance improvements and with enough abstraction around the scary parts it is not even that hard to do. There are projects, such as AsmJit library that provide a very nice way to build optimized functions at runtime and it can be used even in programs that are not just programming language interpreters.

The whole program is available here. Feel free to suggest possible improvements.